For this to happen, a new collaborative approach between the government and the private sector will need to be forged.

ILHAM A HABIBIE

SACHIN V GOPALAN

SHOEB KAGDA

NALIN K SINGH

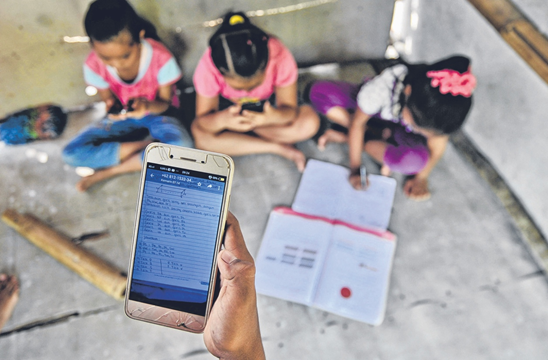

Technology will play an increasingly important role in delivering higher-quality education in Indonesia. The Covid-19 pandemic has already pushed the acceleration of online learning as schools remain shuttered. PHOTO: AFP

For the past decade or so, the foray of the di- gital economy has hogged headlines around the world. Consumers and investors alike have been bowled over by the likes of Uber, Airbnb, WeWork and, closer to home, companies such as Gojek and Grab. These companies have unleashed not just new business models but also changed consumer behaviour in previously unimaginable ways. As underlying principles of the digital economy, commercial sharing and working gigs have become part of today’s world.

But a new paradigm shift is underway, fuelled by the pandemic unleashed by Covid-19. Individuals, companies, industries and governments are waking up to the new reality of social distancing and work-from-home (WFH). Indeed, we may be seeing the start of another principle of the digital economy – physical isolation sustained by ongoing digital life. In times of crisis, people prefer to study, work and entertain themselves at home rather than venturing out. Call it “substituting the physical”, another underlying principle, perhaps, of the digital economy.

According to research, the global pandemic is keeping well over a billion people inside their homes. This is impacting a range of industries, including the education sector as schools and universities remain shut and students are learning to learn online. Change is underway.

Uncertain Outcome

Online education and digitisation of learning have leapfrogged 15 years in the first 15 weeks of 2020. Shared thinking by innovators and technologists has resulted in many new education startups that are emerging all over the globe as these companies rush in to fill an emerging need. But many of these ideas are coming up against entrenched, Old-Economy models and players who are hanging on to their increasingly untenable positions.

While the impact of Covid-19 on the education sector is clear, the outcome remains uncertain. What is clear is that technology and new behaviour patterns will drive change in the sector and may totally revamp how education is consumed and delivered in the future.

Indonesian President Joko Widodo made an unprecedented move in October 2019 to shake up the country’s embattled education sector by appointing a digital tycoon as the new minister of education. Nadiem Makarim, founder of Gojek, is the poster boy for Indonesia’s fast- growing digital economy and it is hoped that he will be able to inject some much-needed innovation and new ideas into the nation’s education sector.

It is not an easy task and the minister has already run up against vested interest groups within the sector. With 60 million students, four million teachers, and 565,000 schools, Indonesia has the largest education system in South-east Asia and the fourth-largest in the world after China, India and the United States.

Access to education therefore is not the key challenge. Indonesia has high literacy rates – 95 per cent of Indonesians can read and write. Where Indonesia lags behind many of its neighbours is in developing graduates with the requisite technical or business skills and knowledge to fill future jobs, especially in the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Indonesia may have a large labour force but it has a very small talent pool. Increasing this talent pool is the biggest challenge facing the country’s education sector. Indonesian students score badly on PISA tests, especially in science and mathematics where it ranks among the world’s lowest. To some extent, the government is already throwing money at the problem, allocating around 21 per cent of its annual budget for education. This accounts for 3.6 per cent of Indonesia’s US$1 trillion pre-Covid-19 gross domestic product (GDP).

Beyond hard cash, however, new ideas have to be injected to boosting education reach and performance. If Indonesia is to be economically competitive in the digital economy, it needs to raise the level and quality of its education product. Therein lies the challenge for the country’s education sector.

The Indonesia Education Forum, a multi-stake- holder platform that brings together more than 1,000 thought leaders and practitioners, has over the past two years been conducting a series of workshops, opinion polls and roundtable discussions to unearth new ideas and thinking that can solve the key challenges facing the industry. These ideas and a white paper on the future of the education sector are being presented to the education minister for his reference and inputs. Suffice to say, the calls for a radical rethink on how education is delivered and consumed in Indonesia going forward were loud and clear.

Firstly, technology will play an increasingly important role in delivering higher-quality education. The Covid-19 pandemic has already pushed the acceleration of online learning as schools remain shuttered. We need to be a game-changer by bringing gamification, digitisation, virtual reality and other emerging technologies into the classroom.

To support this, schools must introduce the smart classroom concept that can run blended learning platforms so that high quality and a standardised education programme can reach even the most remote regions of the archipelago.

But beyond just a means of delivery, Indonesia must also revamp its curriculum to include technology into teaching materials very early on. Future skills for youth will need to include technology literacy, early-stage STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) programmes, and artificial intelligence. Also important is Entrepreneurship for Youth curriculum that is designed as early growth-mindset programmes to help embed soft skills, business acumen and financial savvy into the young minds of future leaders.

Acquiring New Skills

This is where an Education Lab (EduLab) could be established by the Ministry of Education to identify the world’s top education products, programmes and platforms and adapt them accordingly to meet Indonesia’s needs, as well as catalyse local technology, innovation and industry in that regard.

Other important ideas worth exploring include improving teacher resources and training so as to raise technology competence among teachers and enable them to deliver lessons online. The majority of Indonesian teachers do not possess the technological skills to conduct online classes but as the Covid-19 pandemic has taught us, we all need to adapt and acquire new skills.

The education sector and its ancillary services must be classified as a strategic industry and provided resources and fiscal incentives by the central government. Indonesia must move beyond just consuming education products and become a major developer of such products based on its huge domestic sector.

To game-change the education sector, a new collaborative approach between the government and the private sector will need to be forged. No one side can meet these challenges on its own and the education ministry risks trying to achieve these changes on its own.

Indonesia has been offered a unique opportunity to be a leader in this fast-changing field. It must grab the opportunity this current pause offers to roll out farreaching reform in curriculum, the way education is delivered and improving the quality of teachers that will deliver the service. Periods of deep human despair have sparked some of the greatest innovations of humankind.

*The writers are co-founders of the Indonesia Education Forum (IDEF), an independent platform that works with education stakeholders to better understand the future of learning. IDEF is an initiative of The Indonesia Economic Forum, a thought leadership platform aimed at promoting economic and social progress in the country.