Source: The New York Time, October 1 2019

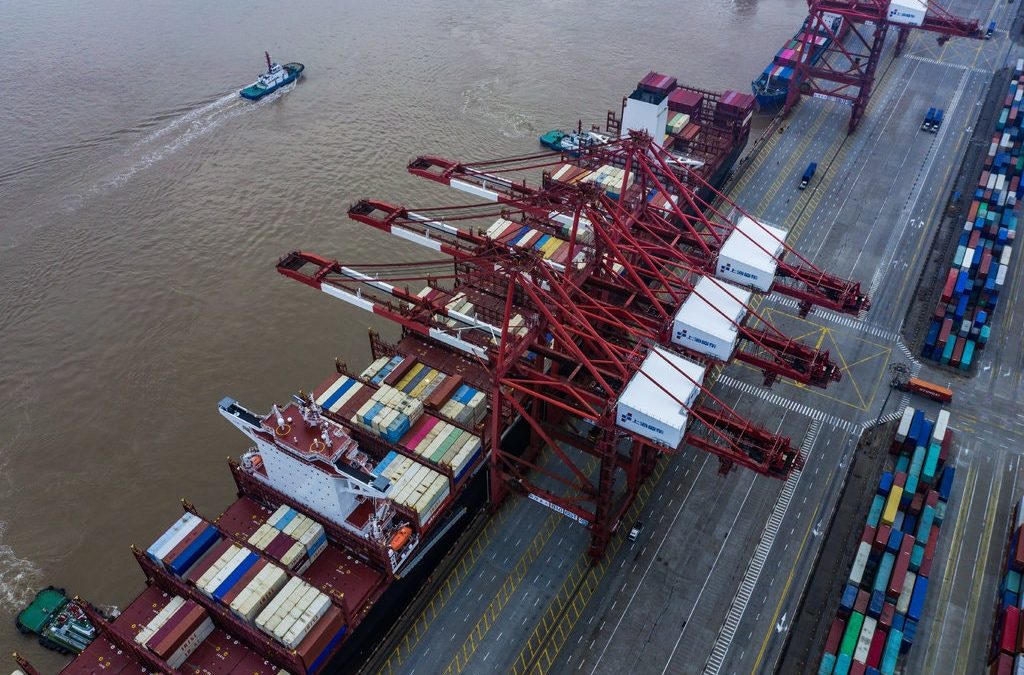

LONDON — As President Trump intensifies his trade war with China, and as factories slow in major industrial nations, world commerce is deteriorating rapidly, a perilous development that threatens the health of the global economy.

A global recession remains unlikely, even as growth slows, most economists say. But the dangers are clearly mounting, threatening to spread from the factory floor to households in many major economies.

The latest sign arrived Tuesday morning, as the World Trade Organization slashed its forecast for trade growth for this year and next.

World trade in merchandise is now expected to expand by only 1.2 percent during 2019, in what would be the weakest year since 2009, when it plunged by nearly 13 percent in the midst of the worst global financial crisis since the Great Depression. Only six months ago, the organization was forecasting more than double that pace of growth, a 2.6 percent expansion in merchandise trade.

The W.T.O. warned that intensifying trade conflicts posed a direct threat to jobs and livelihoods, while discouraging companies from expanding and innovating.

Both the United States and China — the world’s two largest economies — have seen a pronounced cooling in commercial activity in recent months, a trend exacerbated by the tariffs they have imposed on each other’s exports, raising costs for businesses and consumers, and discouraging investment.

In Europe, trade is being stymied by fear that Britain may be on the verge of a tumultuous exit from the European Union, absent a deal governing future commerce across the English Channel.

“Certainly, you can make a strong case that the risks of a global recession have increased the last few months,” said Ben May, a global economist at Oxford Economics, a research institution in London that pegs the likelihood of that outcome next year at 30 percent. “There’s a combination of indicators for weakening global growth. And that means we are more pessimistic about where world trade should trend.”

Later on Tuesday, a closely watched gauge of American manufacturing revealed that factories had slowed in September, marking the second straight month of decline. The reading on the Institute for Supply Management’s manufacturing index was the lowest since June 2009, the month that marked the official end of the Great Recession.

Stocks dropped after that report, eliminating gains seen earlier. Money shifted into Treasury bonds, a traditional safe haven, indicating that investors were willing to accept the prospect of smaller rewards in exchange for refuge from risk.

Prices for crude oil fell, another sign that markets were assuming weaker global economic growth ahead. Less commercial activity spells less need for fuel to power jets, construction equipment, freight engines and other key pieces of industrial life.

Money moved into the dollar, another reach for safety, lifting its value against other currencies. A stronger dollar makes American goods more expensive in world markets compared to those produced in other countries.

President Trump — now embroiled in an impeachment investigation and looking ahead to his re-election bid next year — has long bemoaned the stronger dollar as a threat to American factories. On Tuesday, he took to Twitter to excoriate the Federal Reserve chair he nominated, Jerome H. Powell, blaming him for the strong dollar while accusing the central bank of keeping interest rates too high.

“As I predicted, Jay Powell and the Federal Reserve have allowed the Dollar to get so strong, especially relative to ALL other currencies, that our manufacturers are being negatively affected,” Mr. Trump tweeted. “Fed Rate too high. They are their own worst enemies, they don’t have a clue. Pathetic!”

The Fed, after raising interest rates four times in 2018, has dropped them twice this year, though not enough to satisfy Mr. Trump.

As the Fed lowered rates last month, Mr. Powell said his shift toward easier money had been triggered by concerns that the global economy was weakening, in part because of “trade policy tensions.”

In Fed speak, the central bank chief seemed to be suggesting that Mr. Trump had the power to restore economic vigor himself. He merely had to forswear his trade war.

But few imagined that happening soon, a key reason those in control of corporate accounts from North America to Europe to Asia are becoming less inclined to invest, hire more workers and place orders for factory goods.

“Trade conflicts heighten uncertainty, which is leading some businesses to delay the productivity-enhancing investments that are essential to raising living standards,” the W.T.O.’s director-general, Roberto Azevêdo, said in a statement. “Job creation may also be hampered as firms employ fewer workers to produce goods and services for export.”

Trade will grow by 2.7 percent next year, the organization forecast, a tad below the 3 percent it envisioned in April. Yet this was a moving target, with most of the motion headed in the wrong direction.

“Risks to the forecast are heavily weighted to the downside and dominated by trade policy,” the W.T.O. said in a statement.

In April, when the W.T.O. released its last forecast, sentiments were buoyed by hopes that Washington and Beijing were nearing a deal to resolve their trade disputes. That now seems like a long time ago.

In September, Mr. Trump increased tariffs on $112 billion worth of Chinese imports, threatening American consumers with higher costs for shoes, apparel and electronics. As China slapped retaliatory tariffs on $75 billion of American imports, Mr. Trump threatened to extend tariffs to $550 billion worth of Chinese imports.

The president last month delayed by two weeks a planned increase in tariffs on $250 billion worth of Chinese goods, briefly rekindling hopes for a deal. But many experts are skeptical that an agreement will be struck, amplifying concerns about a range of indicators that the global economy is weakening — including a slowdown in freight and quieter factories.

“The warning signs here are clear enough,” said Ian Shepherdson, chief economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, in a note to clients. “The trade war is wreaking havoc.”

The risk is that a slowdown in factory orders could halt the growth of wages and bring job reductions. Smaller paychecks could prompt Americans to embrace thrift. Given that consumer spending makes up roughly two-thirds of economic activity in the United States, that road could lead to contraction.

“If consumers’ confidence seriously falters, the U.S. could tip into the first recession ever caused directly by the actions of the president, rather than the action of tight monetary policy on an overstretched private sector,” Mr. Shepherdson said.

The trade war is already menacing many economies that are dependent on exports. Singapore’s economy is now contracting. Japan, South Korea and Taiwan all sell large volumes of manufactured goods to China. They have suffered diminished sales as China slows.

“The policy uncertainty about the future and the real enforcement of trade restrictions is starting to be felt in other places,” said Meredith Crowley, an international trade expert at the University of Cambridge in England.

Germany has become a prominent source of concern in Europe as its factory orders plunge, a trend that deepened in September, according to a survey released on Tuesday.

German manufacturing troubles stem in part from the fact that Chinese companies facing tariffs on exports to the United States are shrinking their purchases of German-made machinery. German companies are also reluctant to invest given Mr. Trump’s active threats to expand the trade war to include tariffs on German cars sold in the United States.

As German companies produce and export less, some are cutting jobs. That is likely to dampen German consumer spending, contributing to weakness in other European economies like Spain and Italy.

The W.T.O. singled out as a potent risk the threat that Britain could crash out of the European Union without a deal governing future trade.

Ever since Britain set Brexit in motion through a referendum in June 2016, Europe has faced uncertainty over its future trade dealings. With weeks to go before the deadline, the situation is especially bewildering.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson has vowed to take Britain out of the Europe Union on Oct. 31, regardless of whether he can secure a deal with the authorities in Brussels, and despite widespread assumptions that a no-deal Brexit would entangle trade in bureaucratic and logistical chaos.

He has demanded a scrapping of a provision negotiated by his predecessor, Theresa May, to prevent the reimposition of a hard border separating Northern Ireland, which is part of the United Kingdom, from the independent Republic of Ireland to the south. The Europeans have held firm, while Mr. Johnson has proposed no formal alternative.

But the British Parliament, alarmed by the possibility of an unruly no-deal Brexit, last month adopted emergency legislation that would force Mr. Johnson to seek an extension of the deadline if he failed to strike a deal. Speculation persists that he might opt to ignore that directive, setting up a constitutional crisis. He is also dealing with allegations that, while he was mayor of London, he directed government funds to a woman with whom he was having an affair.

That an election will soon transpire is accepted as a given, but no one knows when.

None of this enhances the motivation of companies to invest in Britain. The British economy contracted between April and June. Across Europe, the spectacle of Britain at once getting poorer and stuck in the Brexit quagmire is not good for business.

“The British situation is much more uncertain today,” said Ms. Crowley, the Cambridge trade expert. “That is feeding into the weakness of trade growth for other European countries.”

Matt Phillips contributed reporting from New York.