By Shoeb Kagda, Founder Indonesia Economic Forum

A battle is raging in Indonesia. As forests burn in Kalimantan and Sumatra, the streets of the nation’s capital have been turned into battle zones as students have launched large demonstrations against what they perceive to be a power grab by the country’s elite.

Almost overnight, President Joko Widodo is facing the toughest challenge in his political career as he prepares to be sworn in for a second five-year term come October. A people’s champion, he is now being accused of siding with oligarchs and an elite class that do not want to be subject to public scrutiny.

The student demonstrations have flared against two specific pieces of legislation – a bill to defang the Corruption Eradication Commission and a broad revision of the Criminal Code which include several proposals favored by hardline Islamists such as banning sex outside marriage, effectively banning gay and lesbian relations and curtailing freedom of expression.

The President has acted quickly to try and restore calm on the streets by calling on Parliament not to pass the new criminal code bill but he has not yet acceded to demands to repeal the anti-corruption bill.

Thousands of students protesting on the streets is never a good omen for any government. We just have to look north to Hong Kong where weeks of demonstrations that were initiated by students have eroded investor confidence and devastated the tourism and hospitality sector.

Since the fall of Suharto in 1998, students have been at the vanguard of democratic reforms in Indonesia. Former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono also had to face large scale student demonstrations during his tenure and he ultimately ceded to their demands.

Many analysts and human rights activists have argued that the two bills in question are regressive and anti-democratic. A battle has started between the country’s democratic forces and the Islamists conservatives. The question is which side does President Jokowi represent?

Will he defend the will of the people or will he succumb to the powerful political allies who make up his governing coalition?

The New York Times reported in its Wednesday September 25thedition that the corruption measure was just one part of a three-pronged effort by the outgoing Parliament to benefit Indonesia’s oligarchs, many of who are from the ‘New Order’.

According to political observers, the real political positions will only show up after the cabinet selection on October 20thwhen those who have lost out create further social disruptions.

There are serious concerns that the next government will be weak as coalition partners already have their sights on the 2024 elections.

“The current protests show that Jokowi is not the darling of the people anymore,” said one political insider. “And public support is especially important when the political environment is becoming more dynamic.”

Economic woes

Amidst the ongoing political crisis, Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati fired a warning shot that tax revenue from January 2019 to August 2019 were sluggish and indicated a slowdown in economic growth.

“This is a sign that taxpayers, especially companies, are not Ok,” she was reported as saying in the Jakarta Post. She added that everyone should be wary as it signales that the economy is weakening.

The finance minister’s warning was backed by a recent World Bank report which noted that growth in Indonesia has been slowing down inline with the global slowdown and a global recession would be damaging to Indonesia’s economic health.

Titled “Global economic risks and implications for Indonesia,” the report said that the global economy is slowing and that a recession looks increasingly likely; given that all the major global economies are facing serious challenges. If growth in China slows down by 1 percentage point, Indonesia’s growth will decline by 0.3 percentage points.

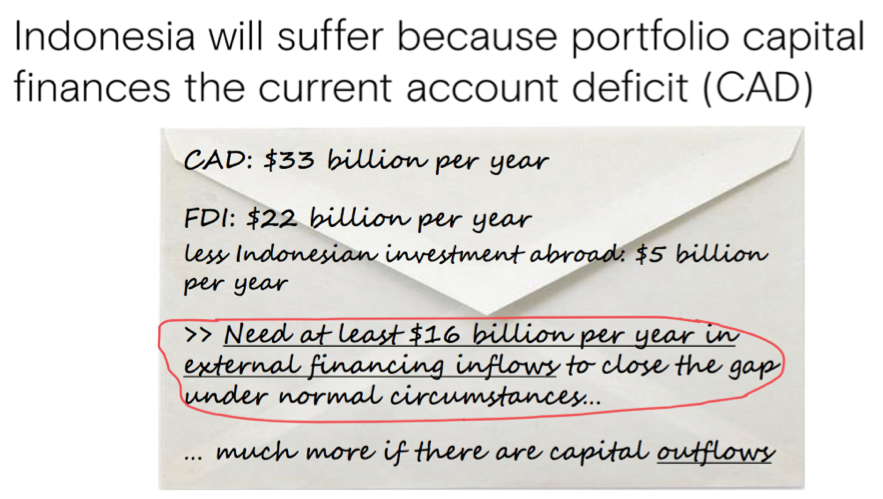

The report warned that these risks could cause a serious negative economic shock with severe portfolio capital outflows. The big danger for Indonesia is that it depends heavily on portfolio capital to finance its current account deficit (CAD). The solution is not to reduce the CAD but to increase Foreign Direct Investments (FDI).

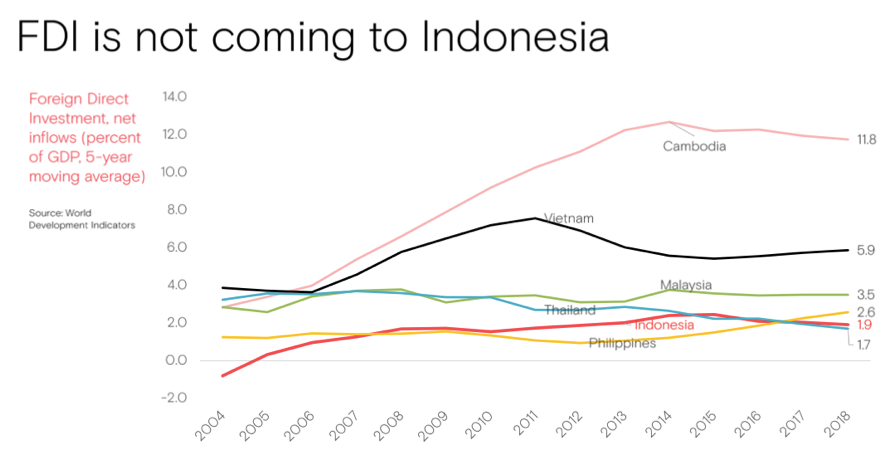

But this is where Indonesia has done poorly. As businesses move out of China to counter the US imposed tariffs, they are giving Indonesia a miss and heading to Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Taiwan because these countries are more welcoming.

Furthermore, Indonesia is cut-off from global supply chains in manufacturing due to its high non-tariff barrier for import of inputs to produce exports. This can be seen by highly discretionary import licenses for hot-rolled steel, tires and pistons. Indonesia’s exports are not competitive because the majority of inputs are subject to import tariffs.

Walking the talk

President Jokowi has said several times that Indonesia welcomes foreign investments and that his government is working hard to improve the business climate and smoothen businesses processes. That message however does not seem to have filtered down to his ministries.

According to the World Bank report, bureaucratic redtape and lack of communications between the ministries is choking the economy.

For example, Bridgestone stopped a production line because the Ministry of Trade and the Ministry of Industry could not decide whether imports of vulnanised tires require a recommendation letter.

There is a gap between the President’s talk and the reality on the ground for businesses and investors. If this is not solved quickly, Indonesia faces a credibility gap which will be difficult to close if investors lose confidence in the country’s policy makers and empty promises.

Policy makers in both parliament and the executive branch should heed these warnings.

Instead of focusing on their own narrow self interests, they should be focusing on passing legislation that welcomes foreign investors; reduces redtape and creates jobs.

In a world that is growing increasingly uncertain, Indonesia still has an opportunity to introduce certainty by passing rules and regulations that are predictable and not discretionary.